Shall We Begin?

Most Sunday afternoons, my parents would play cards with their friends. They’d catch up, reminisce, and ask whatever happened to so and so? Shuffling the deck and picking their teeth, they’d go down the list of which people they had lost in what concentration camps. It was so normal, they may as well have been talking about the weather. Death was implicit in these casual conversations, but it was never the focus. They were so busy re-learning how to be alive and how to forge ahead that talking about the end of life felt taboo. Death cast a long shadow but the very fact that they were living meant that they could outrun it.

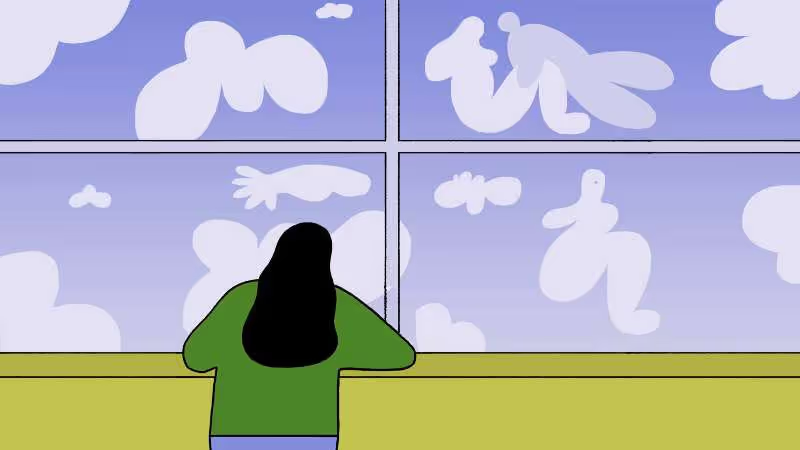

My parents were determined to enjoy life as more than survivors. For them, there was a difference between “not being dead” and “being alive.” Today, it is clear to me that my interest in eroticism—that quality of vibrancy and vitality that beats back deadness—came from that distinction. But it is also clear to me that our avoidance of explicitly talking about death left us utterly unprepared for the event itself. Even now, as I think about grief in the context of this year’s insurmountable losses, I wish I would have asked my parents how they wanted to go and what they thought about how they had lived. Back then, I thought that talking about death was intrusive and, superstitiously, I feared that it would make it come sooner.

When I gave my TED Talk, in 2015, I met fellow presenter Dr. BJ Miller, a palliative care physician whose near-death experience radically changed his view of death. In his talk, BJ articulated how staring at our own mortality or that of our loved one can feel unbearable and yet we must confront it. Doing so, he explained, means placing a greater emphasis on treating people rather than treating illness. It also requires directness. He spoke of a patient at the end of life named Frank who, rather than avoiding the tough conversations, actively engaged in them to “keep up with his losses as they rolled in so that he [was] ready to take in the next moment.”

This was an unfamiliar concept to me. I was raised to compartmentalize and schedule grief into annual religious and spiritual rituals. We complained to blow off steam, but any suffering too heavy to hold on a daily basis was reserved for high holidays. BJ’s words made me wonder about grieving in real time. And ever since then, death has seemed to follow me.

Key people, such Sierra Campbell at Nuture.co, Dr. Jordana Jacobs, and Frank Ostaseski, the founding director of the Zen Hospice Project, came into my life in moments when I was ready to go deeper into the subject of death. In 2017 and 2018, the temple at Burning Man provided me with an immersive, secular ritual of remembrance I’d never known was possible. By day seven, the once empty temple formed a living memorial. In pictures, poems, objects, artwork, and other shreds of lives gone, thousands of people responded to their individual loss and our collective impermanence. I saw the entire drama of human experience laid bare and then burned away.

At End Well, a symposium that unites design, technology, health, policy, and activism to transform thinking around the end of life, I saw another new communal approach to dealing with death. Seeing openness and innovation around such a taboo topic reminded me of how I had felt at my first sexual therapy conference. It was permission to bring the conversation into my professional and personal life. And so I did. A few months later, at a dinner party in Los Angeles, I asked my companions about their experiences with death. The answers were remarkable and I left that evening thinking of all of the future dinner parties I would have where we might talk about death again. I got on a plane home to New York and, within two days, the city went into Covid-19 lockdown. We hadn’t realized at dinner that night how real and immediate the topic would soon become. And I didn’t realize when I came home that night, that I wouldn't be leaving for a very long time.

In March, as New York became the epicenter of the pandemic in the U.S., I realized that the topic I had once avoided—only to become somewhat obsessed with it later in life—was now the most important conversation I needed to have with my family. We needed to talk about death. Over the last few months, we’ve been working with Sierra Campbell to turn the anxiety of “what will we do if” into a plan. Via video call, my husband and I meet with our sons and Sierra. Instead of the usual check in, we talk about checking out. Organization can be a balm in the midst of a chaotic time, and as I hear my family responding to Sierra’s questions, I realize that I am discovering a new tangent in the erotic equation. Talking about death is talking about life—hopes, fears, uncertainty, imagination, legacy, connection, responsibility, love.

I wish I could have had the conversations my sons are having with me now with my own parents. But I am thankful for the conversations we did have, which were emblematic of the way people often confront taboos—through humor. I remember the day my parents came home beaming with joy and said “this is a great day. We bought our plots.” I wondered how anyone could be happy about buying their own burial ground. And then I realized: their families perished in smoke. But they would have a final resting place to call their own, where we could visit them whenever we wanted. That was something to celebrate. Plus, as my mother proudly exclaimed, they had nabbed two of the best plots in the whole cemetery. And you just can’t beat good real estate.

Let’s Turn the Lens on You

Sierra Campbell includes these questions in her crucial conversations about death. They can be asked at any stage of life.

- What are the best and worst case end of life scenarios for myself?

- What am I doing today, in my life, to support best case scenarios?

- What are my views of caregiving?

- Have I ever been a caregiver?

- Has anyone ever really taken care of me?

- How does caregiving impact me, my family, and loved ones?

Let's continue the conversation.

Watch the replay of the Letters From Esther Workshop: What Death Can Teach Us About Life.

More From Esther

Forbidden Conversations / A multidisciplinary training event

Join Esther this November for a three-part digital multidisciplinary training event. Together we’ll explore the concept of taboo and key topics rife with taboos - death, sex, and money - in order to help our communities ask the questions they wouldn't dare to ask, but which are often the most important questions.

Arguing About Money Again? Understanding Financial Tension in Relationships / a recent blog

Talking about money is no easy feat. But, it is an opportunity to understand the deeper beliefs and vulnerabilities it represents in your relationships and to grow your partnerships. Read more about why tensions in your relationship arise around finances and the money questions you can ask to start an open conversation.

Why Do Sexual Taboos Make Up Our Sexual Fantasies? / a recent blog

Our sexual fantasies, and the taboos they contain, are symbolic maps of our deepest needs and wishes. Accessing that vulnerability can turn our sex lives from a ledger into something so much greater, but getting there is a taboo in and of itself. It means talking about it. Read more about sexual fantasies and how they're more normal than you may think.

Conversation Starters

A compendium of highly recommended sources of inspiration and information

On Death:

- Dr. BJ Miller’s TED Talk “What Really Matters at the End of Life”

- Sierra Campbell’s Nurture.Co resources

- “"Til Death do us Part: An Exploration of the Relationship Between Love and Death" by Dr. Jordana Jacobs

- “Tomorrow is Promised to No One: What Death Can Teach Us About Love,” a talk by Dr. Jordana Jacobs

- “The Five Invitations,” a book by Frank Ostaseski

- “The Beauty of What Remains: How Our Greatest Fear Becomes Our Greatest Gift” by Steve Leder, out this January

- Maria Popova’s article “How to Live with Death” (BrainPickings.com)

I’m Reading/Watching:

- “No Shame: Real Talk with Your Kids About Sex, Self-Confidence and Healthy Relationships,” a new book by Dr. Lea Lis

- “The Vow,” a new documentary series that takes an inside look at the sex cult NXIVM

- “7 Deaths of Maria Callas,” an opera project by Marina Abramovic

- “The Social Dilemma,” a new film about the hidden machinations behind social media and search platforms

.svg)